Mexico was the first wine producing region in North America (God bless the missionaries and their vineyards!). While being first doesn’t necessarily suggest a claim to quality, it does lend a certain authenticity to the country’s modern winemaking efforts. Like other “New World” regions, there have been plenty of ups and downs for wine production in Mexico. The last few decades ushered in a notable shift toward modern production methods, however, making Mexico both a very old and very young wine region at the same time.

Valle de Parras

The “Valley of Vines” is the original wine region in the western hemisphere. While Chile and Argentina were close behind, Mexico will always be able to claim this lofty distinction. About 150 miles west of Monterrey, Valle de Parras drew attention from Spaniards for its potential to grow wine grapes. (They even named it after grapes!) While it is currently the home of only a handful of wineries, locals are invested in their history and wineries are working to better meet the preferences of new generations of wine drinkers–both in Mexico and abroad.

The local town of Parras is a delightful place to stay with many restaurant options and warm, inviting residents. While most visitors come from Monterrey and Mexico City, there’s plenty to do for anyone from anywhere who wants to spend a few days in a beautiful environment enjoying wine, local cuisine, and nature.

Casa Madero

The first commercial winery in the Americas, Casa Madero, was established in 1597 by appointment of the Spanish King, Philip II. There is a proud sense of tradition there along with quite a bit of vineyard area (nearly 1,000 acres). Like other legacy wineries, Casa Madero also made brandy in the past, but that is not a current emphasis in production. Most vines are 15-20 years old with a slightly younger organic vineyard as well. Chenin blanc, semillon, gerwürztraminer, chardonnay, merlot, malbec, shiraz, tempranillo, and cabernet sauvignon are all grown onsite. A combination of French and American oak are in use. In a nod to South American wine making (the current head winemaker is Chilean), the malbec spends 2 years in new oak barrels.

Rivero Gonzalez

Another large producer in the area is RG|MX with an expansive estate of 25 year old vines. The entire estate is farmed organically and only native yeast is used for fermentation. I found the wines to be delicious and well made with a particularly exciting “orange” wine made from riesling and palomino grapes. Other varieties grown include chenin blanc, chardonnay, merlot, malbec, syrah, and cabernet sauvignon. Overall, the wines showed the kind of nuance and personality that would please a wide variety of wine enthusiasts.

Vinícola Parvada

The newest entry to the local wine scene is Parvada, envisioned as an entire complex for the production of wine along with residences, lodgings, entertainment, restaurants, and shopping. Not all the development is complete (there are more phases ahead), but the vineyards are planted and a winery of considerable size is up and running. The vines are quite young, so the best years for production definitely lie ahead. Nonetheless, the hospitality (and locally sourced cheese!) were lovely.

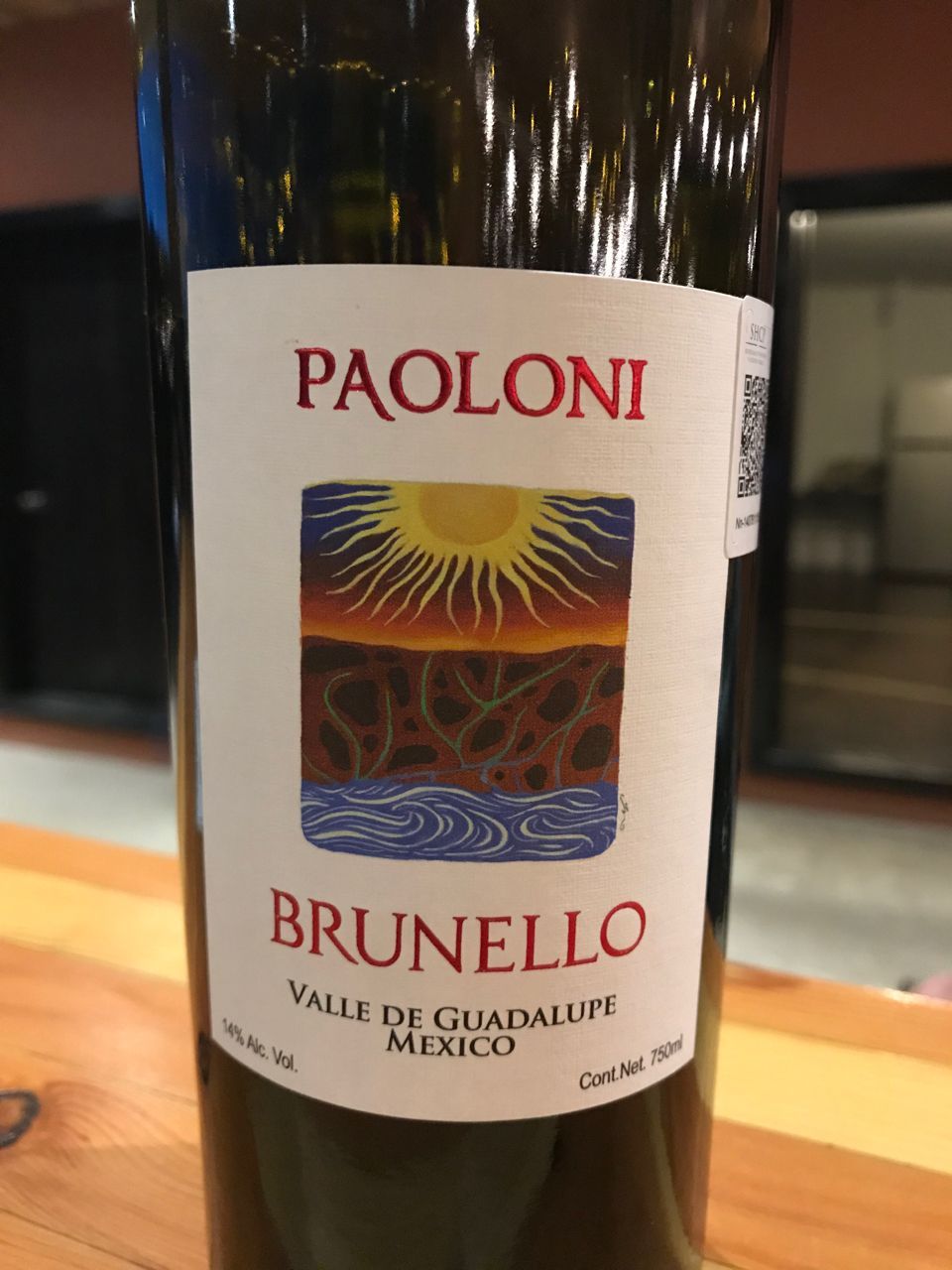

Valle de Guadalupe

Nearly 90% of Mexico’s wine is produced in Baja California (the long “finger” that extends south from the west coast of the USA)–and most of that in the Valle de Guadalupe. With vineyards at the 32nd parallel north, you’ll be hard pressed to identify a serious wine region around the world sharing a similar coordinate (French presence in Algeria and Tunisia once contributed to a focus on wine in those countries but that ended in the middle of the 20th century). Its proximity to the equator makes Baja a marginal climate for wine grape growing so some might doubt its potential.

By way of comparison, the southern hemisphere offers more promise. The 32nd parallel south passes through important wine regions in Chile, Argentina, South Africa, and Australia. These areas would be too hot for quality wine production were it not for the cooling influences of ocean and altitude. Not coincidentally, vineyards in the Valle de Guadalupe are just a short drive from the Pacific Ocean. The elevation is not especially remarkable (the valley floor is 1,500 ft above sea level), but it’s enough to contribute a cooling effect during hot months. Together, ocean breezes and altitude make quality viticulture possible.

Vineyards

The climate in the Valle de Guadalupe is classified as Mediterranean (the abundance of olive trees supports the conclusion) so summers can be quite hot and rainfall is limited. Newer vineyards often incorporate drip irrigation infrastructure and take advantage of planting and trellising methods that allow for the shading and cooling of grapes during the growing season. More traditional plantings of “head trained” (AKA gobelet) vines are also common. Used extensively in hot climates like Spain, these vines are pruned close to the ground where the air is cooler and are trained in such a way that leaves shade grapes from the intense sun. These vineyards are inexpensive to plant (there’s no trellising to install) but labor-intensive to maintain.

Varieties

Given the hot and dry conditions, there are limits to which varieties of wine grapes are fit for the region. Large plantings of tempranillo and grenache are complemented by other warm climate red grapes such as cinsault, mourverdre, and aglianico (all of which are well-represented in the warmer regions of Spain, France, and Italy). Popular international varieties cabernet sauvignon, merlot, and syrah are also planted. There are surprises here and there as well. Nebbiolo and barbera (grapes typically considered best grown in cooler climates) are planted to an unexpected degree in the region.

While a few white varieties like chenin blanc and chardonnay are found here and there, this is not a white wine drinker’s paradise (though pink wines are abundant). In spite of the challenges of the climate (maintaining the lean, acidic profile of many white wines is not easy in hot conditions), growers and winemakers will hopefully embrace opportunities to increase white wine production in the future to round out what the area has to offer.

Finally, while there is no apparent signature grape (or grapes) in the region currently, the degree of experimentation with such a broad array of varieties is commendable. Baja is certainly not the world’s only wine region still sorting out its strengths and weaknesses.

Wineries

There are 130 commercial wine producers in the Valle de Guadalupe, so it can feel overwhelming to choose where to visit.

Melchum, Adobe Guadalupe, Decantos, and Villa Montefiori are certainly worthy of consideration. If you’re in an adventurous mood, a drive south to Baja’s oldest winery

Bodegas Santo Tomás is its own reward. Established in 1888, it was also the first winery in Mexico to have a woman as the head winemaker. In these and many other locations, both the wine and setting are quite lovely. Plus, tasting fees are routinely in the $5 to $15 range. Which is difficult to find in the best American wine regions.

Food

Along with the burgeoning wine industry, an impressive array of excellent dining options dot the valley. From pizza to seafood to authentic Mexican classics, there is hardly a disappointing meal to be found. With a clear understanding that fresh and local ingredients make the best offerings, the standout restaurants in the valley leave a lasting impression. Corona del Valle, Deckman’s,

Hacienda Guadalupe, and the food truck at Adobe Guadalupe are all excellent options. Like the wine, the food is attractively priced for tourists. Similar quality meals are only about half the cost of what would be expected in a major west coast city like Los Angeles or San Francisco.

Final Thoughts

While Valle de Guadalupe offers excellent wine and food at a great value, there are plenty of challenges ahead for Mexican wine. There is a steep tax on wine production (44%!) which creates a context in which Mexican wine enthusiasts are incentivized to purchase imported wine for much less than wine from Mexico. Unfortunately, the government is unlikely to lift this burden as most Mexican wine is made and sold close to the border with the US (meaning many buyers can afford it). This presents a real obstacle for developing a regional wine culture (especially in a country where beer is already so dominant). Let’s hope a powerful senator or other government official takes a personal interest in promoting Mexican wine domestically some time soon so we can all benefit from more of it!

FAQ

Q: Is it safe?

A: You may read or hear about violence in Mexico, but I doubt you’ll ever encounter any. Mexicans are generally lovely people and hospitality is a strong cultural value. Having said that, any place can be dangerous so do exercise common sense and always be aware of your surroundings like anywhere else.

Q: Do I need to speak Spanish?

A: It wouldn’t hurt but it’s not necessary. In Parras, you may need to limp along conversationally while pointing to menu items, etc… Many tasting room employees in Valle de Guadalupe, however, are young people from the nearby city of Ensenada and English is commonly spoken by this demographic.

Q: Don’t Mexicans dislike Americans now?

A: If you’re from the USA, this is a natural question. In spite of current political rhetoric, however, Mexicans don’t seem to hold any of the negativity against visitors. Again, it’s an extremely hospitable country.

Q: How do I get to Parras?

A: With a sense of adventure! Flying into Torreón may be preferable to fighting the traffic in Monterrey. Either way, you’ll need to rent a car or catch one of the occasional regional buses to Paras. The once daily bus ride from Torreón to Parras is 3.5 hours (2 hours direct by car), so don’t get in a big hurry if you opt for this approach. It is certainly an interesting way to experience locals and their vibrant culture.

Q: How do I get to Valle de Guadalupe?

A: If you’re coming from the US or Canada (or maybe anywhere outside of Mexico), you should consider flying into San Diego and renting a car there. Drive inland to cross at the sleepy border checkpoint at Tecate for a scenic drive and easy process. The total drive from the airport to Valle de Guadalupe is about 2.5 hours. A rugged vehicle is highly recommended since all roads (except the main highway) can produce a rough ride.

Q: What’s it going to cost?

A: Lodging is about 75% the cost of what might be expected in west coast areas of the US. There are several levels of accommodations available, however, and luxury options will not be too much of a bargain. As mentioned previously, food is often a value (with no sacrifice in quality).

Have your own Mexican wine experience? We’d love to hear about it (surprising or not). Please

email us.