Our first ever Wine Surprise blog is all about wine from India. Surprise! Few wine drinkers I’ve met realize that India hosts a growing wine industry that has attracted international attention and is producing noteworthy wines. On recent trips to Mumbai, I tasted an array of regional selections. I also visited one of the primary vineyard areas near the city of Nashik (about 3 hours from Mumbai by car) where there are nearly 40 commercial wineries operating in an agricultural area which also supplies much of the produce for the massive population of Mumbai.

A clear take away from up-close observation is that making wine in India is an inherently challenging endeavor. There is very little tradition of winemaking, for example, so every vineyard (and vintage) is a bit of an experiment. This makes the already hard work of winemaking even more exciting and risky. The Indian populace is still developing a taste for wine (you’ll find far more local restaurant patrons enjoying Kingfisher beer), so winemakers don’t receive the same social rewards and recognition as in other more established wine regions. Most difficult of all, of course, is the climate. While tradition can develop and wine appreciation can grow, weather patterns in India are not likely to improve for the purposes of growing quality wine grapes.

Historically, wine regions between 30 and 50 degrees latitude (both south and north of the equator) are recognized as most fit to produce fine wines. This includes the so-called “old world” wine regions of Europe (e.g., France, Italy, Spain, and Germany) along with the most highly regarded wine regions of the “new world” (e.g., USA, Australia, New Zealand, Chile, and Argentina). The wine regions of India are far outside this zone and great care (along with some unorthodox viticultural practices) are required to offset the extreme conditions of heat and precipitation. Left to their own devices, for example, grape vines in this climate will produce two harvests a year. Which may seem like a boon (twice as many grapes=twice as much wine!) but in fact drains the vines of resources to produce high quality fruit and also shortens their overall lifespan.

To address this innate problem, grape growers have adopted specialized farming practices. Grapes are harvested in February and March, then vines are pruned in April. In a typical wine region, vines enter a dormancy period after harvest for the winter ahead. In India, however, the vines produce new shoots (from which new buds would normally grow) almost immediately. To avoid a second crop, growers pull off these new shoots in May heading into the monsoon season (June-September). In September, the vines are pruned again in preparation for the growing season. While the “winter” growing months are relatively cool (by tropical standards), much care must still be taken to protect the vines and fruit from the full effects of the heat and light. In addition to viticultural practices like vine training, elevation and the surrounding rivers and lakes help moderate temperatures in the vineyard.

These growing conditions also present a significant dilemma vis-à-vis regional cuisine. Warm climate grapes from southern Italy, southern France, Spain, and Greece would likely grow best in the Indian heat. These grapes typically contribute to full-bodied tannic wines which would not pair well with most Indian food, however. For example, as a matter of religious conviction, hundreds of millions of Hindus in India do not eat beef. In fact, it is currently illegal for a restaurant to serve beef in India. Even McDonald’s thrives on selling veggie burgers (as well as food from other meat sources such as chicken and fish) in India. There is also a very large population of vegetarians. Finally, as even a casual Indian food diner is aware, the food is often quite spicy (i.e., picante). Put all this together, and it’s clear that lighter bodied wines generally pair better with Indian food. Warm climate grapes, however, produce wines with pronounced body.

The cool climate grape varieties that might pair best with regional cuisine are quite difficult to grow in such a hot climate as India. I tasted a couple of local riesling wines that lacked the crisp acidity normally associated with wines from cooler climates (such as Germany). I also found that red varieties like cabernet sauvignon and shiraz, which require sun and heat to mature, can seem a bit light (even thin at times). This is likely because the grapes were picked before sugar levels were too highly elevated (which would contribute to a high alcohol wine not suitable for pairing with spicy food–or even for drinking at all) and as a result, the fruit doesn’t always develop full flavor potential. This lack of “typicity” in some of the red wines often lends itself to better pairing with regional cuisine, however. Regardless, in a country where sweltering tropical and subtropical climates predominate, full-bodied red wines are unlikely to garner broad appreciation no matter the food style.

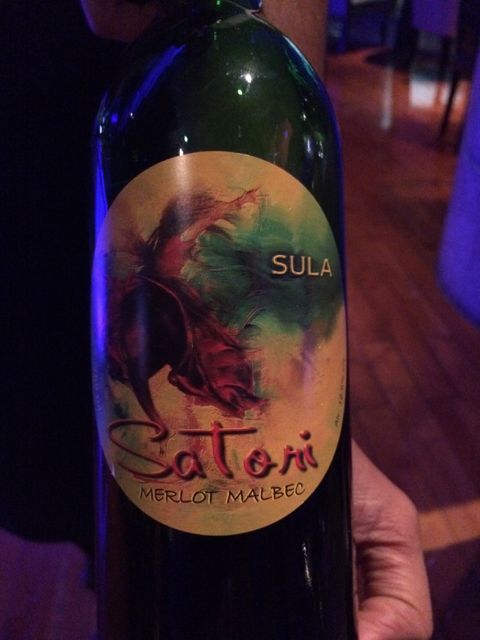

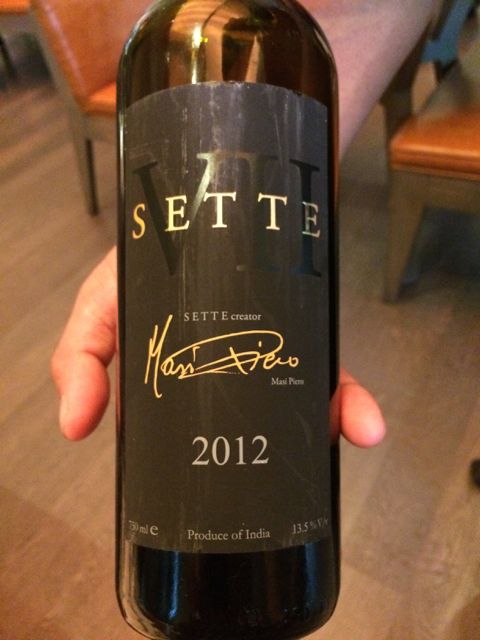

In spite of all these challenges, great things are happening with Indian wine. Three of the larger producers are

Grover Zampa,

Fratelli, and

Sula (all readily available in restaurants in Mumbai). While each of these has been directly influenced by European and American wine-making traditions (French, Italian, and Californian, respectively), the wines are uniquely Indian. While exploring a few wines lists, I especially enjoyed a sparkling chenin blanc from Grover Zampa, the "Sette" Super Tuscan from Fratelli (sangiovese with cabernet sauvignon), and a merlot/malbec blend from Sula. These are all wines I’d be happy to drink again in any country.

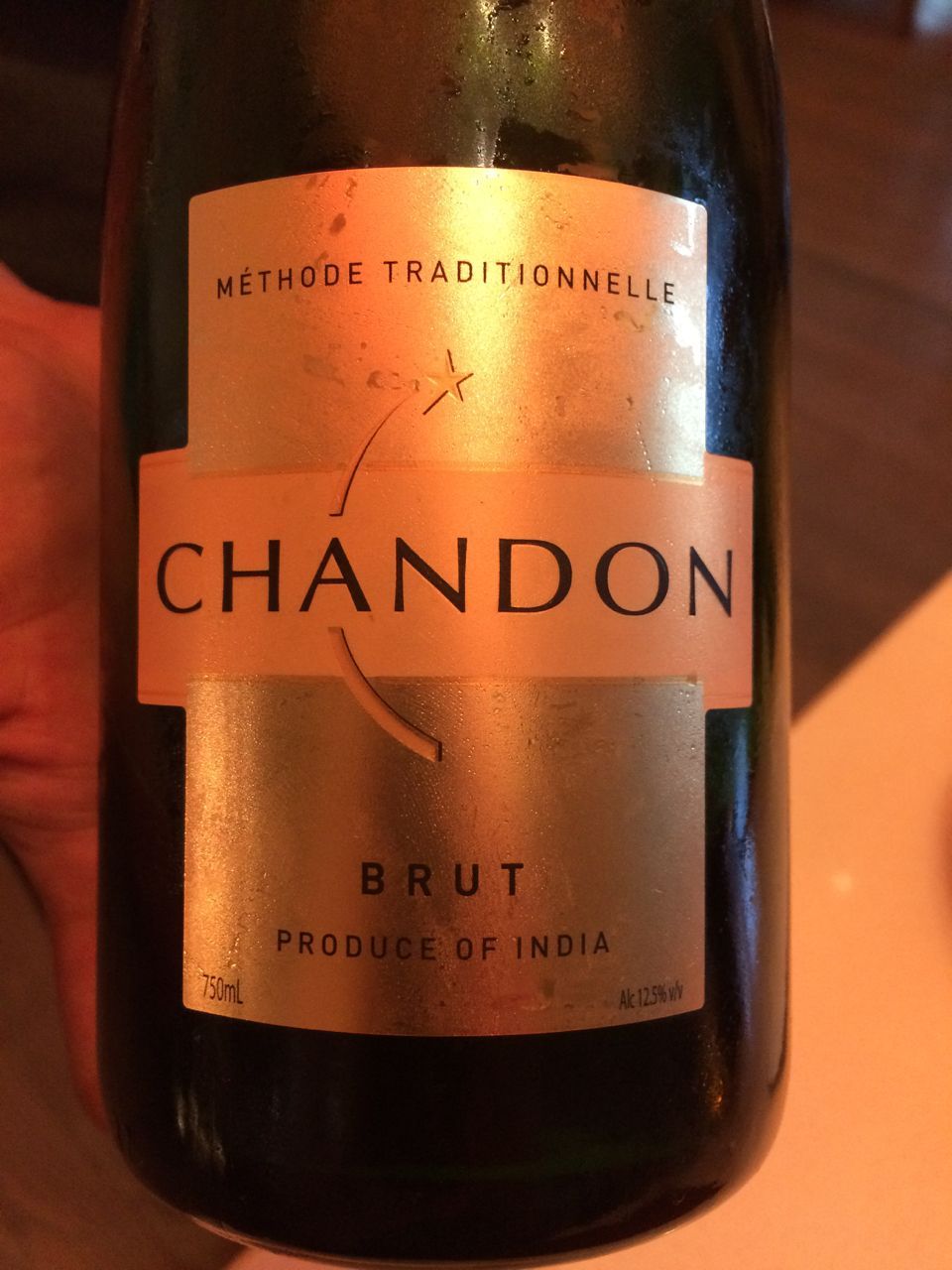

Another well-known producer in India is the international sparkling wine powerhouse

Chandon. In fact, the sparklers I enjoyed in India were the most consistently delightful overall and if there’s a cuisine more suited for pairing with sparkling wine than Inidan, I’ve not met it. The Champagne region in France is a famously cool area for sparkling wine production so India seems an unlikely location for producing such wines. Somehow, Indian producers have identified vineyard sites cool enough for these grapes to prosper. Growers also pick these grapes quite early before too much sugar has developed and the natural acidity has been lost.

The presence of Chandon isn't the only sign of outside influence and interest in Indian wine. Legendary French wine consultant Michel Rolland has been involved with Indian producer Grover Zampa since the 1990s. Grover Zampa’s winery in Nashik has twelve acres planted to viognier, grenache, shiraz, and tempranillo and contracts with local growers each year for additional fruit. (The winery also operates in the Nandi Hills outside of Bangalore where it grows additional varieties like cabernet sauvignon, sauvignon blanc, and chardonnay). The oaky 2015 “La Réserve” (a blend of tempranillo and shiraz) reminded me a of a Rioja and the excellent 2015 “VA” (a blend of shiraz, cab, and viognier named after the Indian tennis player Vijay Amritraj) presented ample fruit, balance, and restrained oak influence. Grover Zampa currently exports to 22 countries.

Valloné VIneyards

is a boutique grower and producer just down the road from Grover Zampa. Hospitable and knowledgeable, head winemaker Sanket Gawand trained in Italy and France before settling in to make wine in his home country. His 2014 syrah/merlot blend was perhaps the most structured of any red wine I’ve tasted from India and his 2014 “Anokhe” (meaning “unique” or “different” in Hindi) was delightfully complex and is made only from exceptional vintages. Valloné’s sweet 2016 “Vin de Passerillage” from chenin blanc also caught my attention with its explosion of apricot and honey on the palate. These grapes are hung and dried inside a straw hut for a month after harvesting until each berry yields only a drop of liquid for wine production, making each taste precious. With an annual total of all varieties produced at less than 6,000 cases, you’ll have to make a trip to India to enjoy these Valloné wines as none are exported.

Though I’m not sure what to expect from India’s wine future, I do admire the extreme passion for and commitment to wine that is necessary to confront the many challenges of such an environment. It’s worth noting that India is currently the fastest growing major economy in the world, so I do think it likely that Indians will continue to develop an interest in wine as fine wine production and developed economies tend to go hand in hand. While further significant experimentation and problem solving will be necessary to produce ultra premium wine in India, we've seen other "new world" wine regions redefine what was once considered possible and I do look forward to following the progress of this upstart wine region.